Volume 13, Issue 2 (5-2025)

Jorjani Biomed J 2025, 13(2): 35-42 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Asadi J, Askari A, Mohammadi Z, Askari B. The experimental model of diet-induced Wistar rat of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Jorjani Biomed J 2025; 13 (2) :35-42

URL: http://goums.ac.ir/jorjanijournal/article-1-1073-en.html

URL: http://goums.ac.ir/jorjanijournal/article-1-1073-en.html

1- Metabolic Disorders Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran; Department of Clinical Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

2- Department of Sport Science, Go.C., Islamic Azad University, Gorgan, Iran

3- Metabolic Disorders Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran; Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, School of Medicine, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

4- Department of Sport Science, Qas.C., Islamic Azad University, Qaemshahar, Iran

2- Department of Sport Science, Go.C., Islamic Azad University, Gorgan, Iran

3- Metabolic Disorders Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran; Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, School of Medicine, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

4- Department of Sport Science, Qas.C., Islamic Azad University, Qaemshahar, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 954 kb]

(454 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2161 Views)

To determine the serum level of triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TCH), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), albumin, and fasting blood glucose (FBS), we used an enzymatic assay through biochemical kits (Mindray BS 480, China) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Also, IL-6 serum level was determined by the chemiluminescence assay method (IMMULITE 2000 Xpi, USA).

Histopathological test

In our study, we employed Hematoxylin and Eosin (H and E) staining to assess the pathology of rat liver. The liver tissues were initially fixed in 10% formalin for 1 hour and subsequently dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Thin sections, measuring 8-10 µm, were obtained from the paraffin-embedded tissues using cryosection techniques (17,18). Following the removal of paraffin, the liver sections were subjected to H&E staining (18) to enable examination under a light microscope for pathological analysis (19). In detail, we performed H and E staining on 5 sections per rat and then randomly selected 10 microscopic fields to investigate the morphological changes in liver tissues. This approach allowed us to precisely assess the pathological characteristics. Additionally, to evaluate the presence of lipid droplets, we utilized Oil Red O (ORO) staining (18). To identify lipid droplets in liver tissue, frozen sections were stained with Oil Red O solution for 15 minutes, then washed with 60% isopropanol and counterstained with hematoxylin. Under the microscope, lipids were observed in red and nuclei in blue. This method can only be applied to frozen tissues because the paraffin deparaffinization process causes lipids to dissolve. Under light microscope assessment, lipid droplets appeared red, while the nuclei were stained blue (19). We determined macrovesicular steatosis grades in the NAFLD-induced group using the following scales: Grade zero, absence of steatosis; grade one, up to 30% of hepatocytes affected; grade two, 30 - 70% of hepatocytes affected; grade three, more than 70% of hepatocytes affected (20).

In this study, solid vegetable oil (Hydrogenated) of palm origin with a purity of 99.8% was used, which was obtained from the local market in Iran. This oil was without any antioxidant or preservative additives. The solid sugar used was prepared from sucrose varieties with a purity of 99.9% (Produced from sugar beet), which was obtained from the same source. The purity of the materials was determined using the manufacturer's certificate of analysis and in accordance with the National Standards of Iran (ISIRI) for vegetable oil (ISI 4094) and sugar (ISIRI 2685). Control group rats were fed a standard basal diet (Commercial pellet containing approximately 3.6% fat, 22% protein, and 50% carbohydrate) for 10 weeks. NAFLD model rats received a combination supplement containing 30% hydrogenated solid vegetable oil (Palm origin) and 10% solid sugar (Sucrose) in addition to the basal diet (21). In this study, histopathological evaluations were performed in a blinded manner by pathologists who were unaware of the animal grouping.

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine the normality of the data. The Levene test was used to determine the homogeneity of the data. Comparisons were made using the independent Student's t-test for two groups (SPSS V.22, New York, USA). Values were determined as Mean ± SEM and were used for analysis throughout the experiment. The significance level was set at P-Value<0.05.

Results

Weight/Time progress and abdominal circumference

To determine the effect of consumption of 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar on weight gain, we evaluated the weight/time progress in the NAFLD-induced group compared to the control group (Figure 1A). The obtained results revealed a significantly increased weight/time progress in the treatment group (0.679 g ± 0.02, P-Value < 0.001) compared to the control group (0.559 g ± 0.03). Based on these results, the weight/time progress of NAFLD-induced rats was higher than that of the control group, indicating that the high-fat/high-sugar diet caused an increase in fat mass in the NAFLD-induced rats.

Additionally, we measured the abdominal circumference at the beginning of the experiment and after ten weeks in both experimental (NAFLD-induced) and control rats. The results illustrated a significant difference in abdominal size between the experimental rats (17.93 cm ± 1.18) and controls (14.82 cm ± 14.82). Furthermore, we calculated the abdominal-to-chest size ratio in both groups. The results showed a significant difference between the NAFLD-induced group (1.17 ± 0.05) and controls (1.07 ± 0.05; Figure 1B). Therefore, these results indicate that the high-fat/high-sugar diet induced abdominal fat accumulation in the experimental group compared to controls.

Effect of high fat/high sugar on glucose serum level

The effect of consuming 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar for ten weeks suggested that glucose intolerance may occur and indirectly increase the incidence of insulin resistance. Fasting blood glucose (FBS (mg/dL)) was significantly increased in NAFLD rats (129.6 ± 32.26, P-Value = 0.001) compared with the control group (67.6 ± 37.91; Figure 2). In conclusion, these data suggest that consuming a high-fat/high-sugar diet could lead to insulin resistance and impaired fasting glucose.

Effect of high fat/high sugar on lipid profile parameters for dyslipidemia

The consumption of a high-fat/high-sugar diet significantly increased TG and CH serum levels in NAFLD-induced rats compared with control rats after ten weeks: 65.400 ± 17.12, P-Value = 0.005; 190.500 ± 29.23, P-Value = 0.001, respectively, compared with the control group: 42.400 ± 14.77 and 138.200 ± 23.74 (Figures 3A and 3B). As expected, these data support the lipid accumulation hypothesis in NAFLD-induced rat livers.

Serum levels of HDL, c-LDL, and v-LDL were also significantly altered in NAFLD-induced rats compared with healthy rats after ten weeks: 48.600 ± 30.86, P-Value = 0.014; 137.400 ± 70.83, P-Value = 0.008; and 13.08 ± 3.42, P-Value = 0.005, respectively, compared with the control group: 96.200 ± 38.45, 63.300 ± 34.99, and 8.48 ± 2.95 (Figures 4A, 4B, and 4C). Our results suggest that increasing 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar in the standard pellet diet is reflected in an elevation in serum lipid profile parameters.

Moreover, the atherogenic index and risk factor were assessed by formula. The results showed a significant increase in NAFLD-induced rats compared to healthy rats. The values of the atherogenic index (c-LDL/HDL) were 4.18 ± 4.00, P-Value = 0.03, and the risk factor (CH/HDL) was 5.74 ± 3.93, P-Value = 0.006 (Figures 5A and 5B). Briefly, the 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar diet could increase coronary atherosclerosis and heart attack risk in NAFLD-induced rats compared to controls.

Furthermore, our findings indicated that the TG/HDL-C ratio and TG serum levels - known markers of insulin resistance - were significantly increased in the NAFLD-induced rats compared to controls. The TG/HDL-C ratio of NAFLD-induced rats was 1.84 ± 1.12 g, whereas in controls it was 0.62 ± 0.55 g, with P-Value = 0.006 considered significant (Figure 5C).

Effect of High fat/high sugar on hepatic enzymes and albumin serum levels

We found that the ALT and AST serum levels of the treatment group were influenced by the 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar regimen. After ten weeks of treatment in the NAFLD-induced group, the serum levels of ALT and AST (IU/L) were significantly increased (349.44 ± 45.3, P-Value = 0.001; and 109.84 ± 24.61, P-Value = 0.001, respectively) compared to healthy Wistar rats (221.95 ± 65.63; and 73.12 ± 17.33, respectively; Figures 6A and 6B). The increases in ALT and AST serum levels indicated hepatic steatosis in NAFLD model rats (Figure 6C). As well, the serum level of ALT was higher than the AST level. Additionally, the obtained results illustrated that the serum level of albumin (g/dl) was decreased in NAFLD-induced rats (3.00 ± 0.65, P-Value = 0.004) compared to controls (3.88 ± 0.50; Figure 7A).

According to the role of interleukin-6 (IL-6) in the progression of NAFLD, we assessed the IL-6 serum level in both groups. In this regard, the serum level of IL-6 was determined by sandwich ELISA. The obtained results revealed that IL-6 levels were significantly increased in NAFLD-induced rats (1.95 ± 0.43 pg/mL, P-Value = 0.004) compared to controls (1.38 ± 0.32 pg/mL; Figure 7B). This was associated with NAFLD induction in NAFLD-induced rats. This result indicates that IL-6 may be a biomarker to describe the risk of NAFLD. The cause of this finding may be that fatty liver itself induces a local subacute inflammatory state characterized by the production of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α or IL-6. These mediators directly contribute to hepatic and systemic insulin resistance (22).

Histopathological results confirmed grade two of hepatic steatosis in high fat/high sugar rats

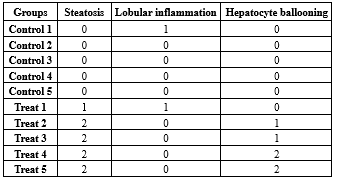

Examination of sections obtained from livers of the healthy group showed normal histological structure. Predominantly, NAFLD is characterized by macrovesicular steatosis that is usually present in grade two. NASH is described by the presence of hepatocellular ballooning, inflammation, and finally fibrosis in the context of a steatotic liver. After ten weeks on the diet, the results obtained from H and E (Figure 8A) and Oil Red O (Figure 8B) staining illustrated that the Wistar rats developed grade two hepatic steatosis with hepatocyte ballooning compared to the control group with grade zero and no lobular inflammation or hepatocyte ballooning (Table 2). These data revealed that treatment with a high fat/high sugar diet could induce NAFLD in Wistar rats compared to controls.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to investigate the effect of a diet containing 30% vegetable oil combined with 10% solid sugar on NAFLD induction in Wistar rats. This study showed that a diet high in vegetable oil and solid sugar, similar to the current human dietary pattern, was able to induce obesity-related NAFLD in Wistar rats, characterized histologically by hepatic steatosis and ballooning of cells. Hepatic changes were clinically characterized by increased TC, and weight/time and metabolic progression were demonstrated by hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, decreased serum albumin, increased IL-6, and elevated serum levels of liver enzymes.

The present findings of steatosis, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and elevated inflammatory markers align with the established pathophysiology through which high-fat/high-sucrose diets promote NAFLD. The combination of saturated fat (From solid vegetable oil) and sucrose acts synergistically via several mechanisms to drive hepatic lipid accumulation and hepatocyte stress. Firstly, high sucrose intake (Hydrolyzed to glucose and fructose) significantly upregulates hepatic de novo lipogenesis (DNL) by activating key transcriptional factors such as ChREBP (23,24). Fructose, in particular, bypasses the tight metabolic regulation of glucose and is rapidly metabolized in the liver, providing ample substrates for DNL (25). Secondly, dietary saturated fat not only provides a direct source of fatty acids for hepatic storage but also promotes peripheral insulin resistance (e.g., in adipose tissue and muscle). This leads to an increased influx of non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) into the liver, providing further substrate for triglyceride synthesis and steatosis (22). Thirdly, this metabolic milieu (Insulin resistance and enhanced DNL) induces oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, as indicated by the elevated liver enzymes (ALT and AST) in our model. This stress activates pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, which we found significantly elevated, creating a vicious cycle that perpetuates both systemic inflammation and hepatic insulin resistance (26).

Thus, our model, by mimicking a relevant human dietary pattern, simultaneously targets key drivers of NAFLD pathogenesis-increased hepatic lipid load, impaired insulin signaling, and inflammatory stress-making it a translationally relevant model for studying this complex disease. Despite the value of existing models, many fail to recapitulate this multifaceted pathophysiology (27).

As well, fewer studies have induced NAFLD in rodents by the simultaneous use of solid sugar and vegetable oil, but in this study, we induced NAFLD through a diet containing 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar for ten weeks in Wistar rats. Other animal studies have described the rapid induction of obesity due to the administration of a high-calorie, high-fructose, and/or high-fat diet, either as a liquid in a food dish or via a nasogastric tube. In contrast, we produced a diet balanced in protein, lipid, carbohydrate, vitamin, and mineral content, which was highly palatable and high in fiber. Practically, we fed animals with a diet very similar to a normal diet both in content and form of administration. In our study, free access to a diet containing 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar was available for NAFLD-induced rats (28,29).

The hyperinsulinemia caused hepatocytes to produce more fatty acids, and triglyceride accumulation in hepatocytes subsequently led to steatosis. It is important to note that a diet with high carbohydrate content aggravates de novo hepatic lipogenesis and plays a critical role in glucose homeostasis, accelerating the development of hypertriglyceridemia and hyperinsulinemia (23,24). Specifically, when the amount of carbohydrates consumed exceeds the total caloric requirement, the rate of de novo hepatic lipogenesis increases more than 10-fold (25). Likewise, it increases 27-fold by consuming a high-carbohydrate diet compared to low-carbohydrate diets and/or fasting (25).

Also, our results have shown that the high-fat/high-sugar diet could increase cardiovascular diseases and was associated with augmentation of atherogenic factors in NAFLD model rats (30). In addition, due to the pro-atherogenic lipid profile, this disease is associated with increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, which we also found in our study (31).

Since we illustrated decreased serum levels of albumin in NAFLD model rats compared to controls, however, it was not significant. The serum level of albumin was associated with NAFLD induction and impaired glucose tolerance. There is a positive correlation between serum albumin level and metabolic syndrome or metabolic risk factors such as lipid profile and BMI. This finding suggests that serum albumin level is associated with insulin resistance (31-33). Aligning with our study, several studies have shown a protective effect of albumin on cardiovascular health, as low levels of serum albumin were associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease, cardiovascular mortality, and carotid atherosclerosis (32,34). One possible explanation for this association is the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of serum albumin. Chronic inflammation plays an essential role in causing insulin resistance and the occurrence of NAFLD (32,34). The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory characteristics of serum albumin in the atherogenic process are suggested as possible mechanisms for this association. As well, chronic inflammation plays essential roles in the generation of both insulin resistance and NAFLD (35-38).

Furthermore, our results illustrated that the serum levels of AST and ALT increased in rats that received the NAFLD-induced diet, indicating successful establishment of the NAFLD model. Previous studies have shown that mild to moderate serum AST and ALT levels increase in patients with NAFLD (39). Several studies demonstrated that the biochemical pattern in hepatic steatosis due to NAFLD is characterized by increased levels of transaminases, with ALT levels exceeding those of AST. Consequently, our results revealed that the serum level of ALT was higher than AST in NAFLD model rats, confirming the formation of steatosis in NAFLD model hepatic tissue (40,41).

Hepatic steatosis and hepatocellular ballooning-early stages of NAFLD-were present in all liver samples of the rats from week 10. At the final stage of the investigation, grade 2 steatosis was observed at week 10. Moreover, fatty droplet formation, confirmed by Oil Red O staining, indicated hepatic injury and lipid accumulation in NAFLD model rats. However, the study duration may not have been long enough to allow for more severe steatosis and histological changes to characterize NASH. Since the liver lesions that occur in NAFLD are associated with the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the liver such as IL-6, our results illustrated that the serum levels of IL-6 increased in NAFLD rats compared to controls.

Furthermore, histopathological examination provided detailed visualization of liver architecture in both groups. The control group exhibited normal lobular organization, with intact hepatocyte cords, distinct sinusoids, and no evidence of lipid accumulation or ballooning degeneration. In contrast, liver sections from NAFLD-induced rats showed marked macrovesicular and microvesicular steatosis, characterized by large cytoplasmic fat vacuoles displacing the nuclei to the cell periphery. Ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes and mild inflammatory cell infiltration were also observed. Oil Red O staining confirmed the presence of abundant red-stained lipid droplets within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes, consistent with fat accumulation and hepatic injury. These observations confirmed the successful induction of grade II hepatic steatosis. Scale bars represent 50 μm in all histological images.

Furthermore, we observed steatosis and hepatocellular ballooning denoting cell injury, revealing NASH histologically. Subsequently, the model presented in this study illustrated that a diet containing 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar induces NAFLD, which is associated with elevated serum levels of FBS, lipid profile, ALT, AST, IL-6, and weight/time progress. Moreover, the incidence of NAFLD in treated rats compared to the control group was confirmed by H&E and Oil Red O staining. The 10-week duration of this study may not fully replicate advanced human NASH with fibrosis, and the exclusive use of male rats limits understanding of gender differences.

Conclusion

In this study, we developed the NAFLD model in rats through the administration of standard pellets supplemented with 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar and obtained biochemical and histological results that confirmed the formation of grade 2 steatosis in NAFLD model rats.

Future directions

Future research should include longer studies to observe fibrosis progression, include female subjects to examine gender disparities, and perform molecular analyses to elucidate underlying pathways.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Golestan, Iran, for providing the facility for performing the animal experiments.

Funding sources

This study was supported by Golestan University of Medical Sciences under grant number [Ethic code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1402.063], which had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Ethical statement

All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (IR.GOUMS.REC.1402.063). The study was conducted in full compliance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

J.A. and A.A. Designed and implemented the study. A.A, and B.A. Performed the experiments and collected the data. A.A. and Z.M. Performed the analysis and interpretation of the data. Z.M. Drafted the manuscript. A.A., Z.M., and B.A. Critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Full-Text: (211 Views)

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has rapidly emerged as a global health priority and a leading cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality worldwide (1). Its prevalence is particularly high in regions such as South Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America, exceeding 30% in some populations (2). A recent meta-analysis reported an annual incidence rate of 50.9 per 1000 person-years in Asia (3), with rates estimated to be 27.88% and 30.17% in Iran for women and men, respectively (4). The increasing incidence of NAFLD is closely intertwined with the global epidemic of metabolic diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance (5,6). The pathological spectrum of NAFLD ranges from simple hepatic steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (7,8). The modern Western diet, characterized by highly processed foods rich in saturated fats and refined sugars, is one of the major known factors in the development and progression of NAFLD (5). Diets high in saturated fat and simple carbohydrates, such as sucrose, promote dyslipidemia and fatty liver (5).

However, a comprehensive understanding of the etiology and pathobiology of NAFLD in humans remains challenging due to the heterogeneity of the disease and the difficulties associated with early diagnosis and longitudinal monitoring.

Role and limitations of rodent models

Given these challenges, rodent models have become essential tools for NAFLD research, as they can recapitulate key histopathological features of the human disease and provide insights into its progression (9). An ideal animal model should mimic human pathophysiology by demonstrating the main features of NAFLD, including insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis (10,11). While high-fat or high-sucrose diets are commonly used to induce NAFLD, the resulting phenotypes can be highly variable and often result in mild liver inflammation and limited fibrosis (12). For example, some studies using high-fructose or high-cholesterol diets have reported only grade 1 steatosis (13,14), highlighting the need for more robust and reproducible models that better reflect the human condition.

Although studies have shown that the combination of fat and sucrose can promote NAFLD in rodents (15,16), the specific effects of a diet containing solid vegetable oil (A source of saturated fat) and solid sugar (Sucrose) - which mimics a common and high-risk human dietary pattern - are still unclear. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to establish a novel dietary model of NAFLD in Wistar rats using a diet containing 30% solid vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar. We hypothesized that this diet would effectively induce key features of NAFLD, including significant metabolic abnormalities (Dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia), elevated liver enzymes, increased systemic inflammation (IL-6), and histologically confirmed hepatic steatosis.

By simulating a relevant dietary pattern, this model aims to provide a valuable tool to investigate the pathophysiology of NAFLD and test potential therapeutic interventions. Also, the study by Torres-Villalobos et al. demonstrated that grade II and III steatosis developed in rats fed a high-cholesterol diet, while rats fed a high-sucrose diet developed grade 1 steatosis (16).

Although the cause of NAFLD is not fully understood, changes in dietary composition are believed to play an important role in the development of the disease. Diets with high levels of saturated fat, cholesterol, and non-complex carbohydrates (e.g., disaccharides such as sucrose) have been shown to induce dyslipidemia and fat accumulation in the liver and are suggested to play a key role in the development of NASH in humans (15). Nonetheless, more studies are required to better understand these differences. However, as far as we know, it is unclear whether diets of this type - usually associated with 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar in rats or humans - cause obesity and insulin resistance or not.

Therefore, in this study, we emphasize the important role of combining animal fat in the diet with high sucrose in inducing NAFLD in Wistar rats. The present study, with innovative results, investigates the combined effect of solid vegetable oil and solid sugar on the induction of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the Wistar rat animal model. This study, for the first time, examines the pathophysiological mechanisms resulting from these diets by simulating a high-risk nutritional pattern common in society (Saturated compounds and simple sugars).

Methods

Ethics statement

All the protocols of this study were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (IR.GOUMS.REC.1402.063) and were carried out based on the regulations of the National Institute of Health for the care and use of animals in research. The protocol for the animal research project was approved by Golestan University of Medical Sciences. Also, we followed the protocol for the animal research project according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUCs) based on these steps (Briefly): (1) Animal housing and care, (2) Ethical considerations, (3) Experimental procedures, (4) Reporting and documentation, and (5) Compliance with local regulations.

Reagents

The AST, Cholesterol, Triglyceride (TG), and FBS kits were obtained from Darman-faraz-kave Company (Tehran, Iran). In addition, we purchased the ALT, HDL, and Albumin kits from Padco, Pishtaz-teb, and Pars-Azmon Company (Tehran, Iran), respectively. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels in serum samples were measured using a chemiluminescent immunoassay kit on an IMMULITE 2000 Xpi automated system (Manufactured by Siemens Healthineers, USA). This method uses a sandwich immunoassay in which a solid phase-bound antibody binds to the IL-6 molecule and a second antibody conjugated to the alkaline phosphatase enzyme is used to detect and form a sandwich complex. After addition of a fluorescent substrate (Dioxetine) and cleavage by the enzyme, light is produced, the intensity of which is directly related to the IL-6 in the sample. The final results were plotted against a calibration curve and interleukin-6 was expressed in picograms per milliliter (pg/mL).

Animals experiment

Twenty male Wistar rats, 8-10 weeks old, body weight 181.7 ± 33 g, were purchased from the Pasteur Institute (Tehran, Iran). Rats were randomly divided into two groups (n = 10 per group): Group one is the control group with free access to water and standard pellet food (Table 1), and group two is the NAFLD-induced group with free access to water and inducible-NAFLD pellets. To acclimatize rats, we performed 12 h dark-light cycles in a temperature-controlled facility (22°C ± 1.4°C, and 55 ± 4% relative humidity) at the Laboratory Animal Centre of Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Golestan, Iran. Initially, rats had free access to standard pellets (10 g of standard food per 100 g body weight) and water. After one week of adaptable feeding, we added 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar to standard pellets to induce the NAFLD model in the inducible-NAFLD group. The experiments went on for ten weeks, and blood samples were taken from the heart after the rats were sacrificed by inhaling CO₂. To perform the biochemical analysis, the serum was isolated from blood samples and immediately stored at -80°C. Moreover, tissue samples were isolated and immediately stored at -80°C for H&E staining. Besides, the body weight of each rat was recorded weekly.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has rapidly emerged as a global health priority and a leading cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality worldwide (1). Its prevalence is particularly high in regions such as South Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America, exceeding 30% in some populations (2). A recent meta-analysis reported an annual incidence rate of 50.9 per 1000 person-years in Asia (3), with rates estimated to be 27.88% and 30.17% in Iran for women and men, respectively (4). The increasing incidence of NAFLD is closely intertwined with the global epidemic of metabolic diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance (5,6). The pathological spectrum of NAFLD ranges from simple hepatic steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (7,8). The modern Western diet, characterized by highly processed foods rich in saturated fats and refined sugars, is one of the major known factors in the development and progression of NAFLD (5). Diets high in saturated fat and simple carbohydrates, such as sucrose, promote dyslipidemia and fatty liver (5).

However, a comprehensive understanding of the etiology and pathobiology of NAFLD in humans remains challenging due to the heterogeneity of the disease and the difficulties associated with early diagnosis and longitudinal monitoring.

Role and limitations of rodent models

Given these challenges, rodent models have become essential tools for NAFLD research, as they can recapitulate key histopathological features of the human disease and provide insights into its progression (9). An ideal animal model should mimic human pathophysiology by demonstrating the main features of NAFLD, including insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis (10,11). While high-fat or high-sucrose diets are commonly used to induce NAFLD, the resulting phenotypes can be highly variable and often result in mild liver inflammation and limited fibrosis (12). For example, some studies using high-fructose or high-cholesterol diets have reported only grade 1 steatosis (13,14), highlighting the need for more robust and reproducible models that better reflect the human condition.

Although studies have shown that the combination of fat and sucrose can promote NAFLD in rodents (15,16), the specific effects of a diet containing solid vegetable oil (A source of saturated fat) and solid sugar (Sucrose) - which mimics a common and high-risk human dietary pattern - are still unclear. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to establish a novel dietary model of NAFLD in Wistar rats using a diet containing 30% solid vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar. We hypothesized that this diet would effectively induce key features of NAFLD, including significant metabolic abnormalities (Dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia), elevated liver enzymes, increased systemic inflammation (IL-6), and histologically confirmed hepatic steatosis.

By simulating a relevant dietary pattern, this model aims to provide a valuable tool to investigate the pathophysiology of NAFLD and test potential therapeutic interventions. Also, the study by Torres-Villalobos et al. demonstrated that grade II and III steatosis developed in rats fed a high-cholesterol diet, while rats fed a high-sucrose diet developed grade 1 steatosis (16).

Although the cause of NAFLD is not fully understood, changes in dietary composition are believed to play an important role in the development of the disease. Diets with high levels of saturated fat, cholesterol, and non-complex carbohydrates (e.g., disaccharides such as sucrose) have been shown to induce dyslipidemia and fat accumulation in the liver and are suggested to play a key role in the development of NASH in humans (15). Nonetheless, more studies are required to better understand these differences. However, as far as we know, it is unclear whether diets of this type - usually associated with 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar in rats or humans - cause obesity and insulin resistance or not.

Therefore, in this study, we emphasize the important role of combining animal fat in the diet with high sucrose in inducing NAFLD in Wistar rats. The present study, with innovative results, investigates the combined effect of solid vegetable oil and solid sugar on the induction of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the Wistar rat animal model. This study, for the first time, examines the pathophysiological mechanisms resulting from these diets by simulating a high-risk nutritional pattern common in society (Saturated compounds and simple sugars).

Methods

Ethics statement

All the protocols of this study were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (IR.GOUMS.REC.1402.063) and were carried out based on the regulations of the National Institute of Health for the care and use of animals in research. The protocol for the animal research project was approved by Golestan University of Medical Sciences. Also, we followed the protocol for the animal research project according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUCs) based on these steps (Briefly): (1) Animal housing and care, (2) Ethical considerations, (3) Experimental procedures, (4) Reporting and documentation, and (5) Compliance with local regulations.

Reagents

The AST, Cholesterol, Triglyceride (TG), and FBS kits were obtained from Darman-faraz-kave Company (Tehran, Iran). In addition, we purchased the ALT, HDL, and Albumin kits from Padco, Pishtaz-teb, and Pars-Azmon Company (Tehran, Iran), respectively. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels in serum samples were measured using a chemiluminescent immunoassay kit on an IMMULITE 2000 Xpi automated system (Manufactured by Siemens Healthineers, USA). This method uses a sandwich immunoassay in which a solid phase-bound antibody binds to the IL-6 molecule and a second antibody conjugated to the alkaline phosphatase enzyme is used to detect and form a sandwich complex. After addition of a fluorescent substrate (Dioxetine) and cleavage by the enzyme, light is produced, the intensity of which is directly related to the IL-6 in the sample. The final results were plotted against a calibration curve and interleukin-6 was expressed in picograms per milliliter (pg/mL).

Animals experiment

Twenty male Wistar rats, 8-10 weeks old, body weight 181.7 ± 33 g, were purchased from the Pasteur Institute (Tehran, Iran). Rats were randomly divided into two groups (n = 10 per group): Group one is the control group with free access to water and standard pellet food (Table 1), and group two is the NAFLD-induced group with free access to water and inducible-NAFLD pellets. To acclimatize rats, we performed 12 h dark-light cycles in a temperature-controlled facility (22°C ± 1.4°C, and 55 ± 4% relative humidity) at the Laboratory Animal Centre of Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Golestan, Iran. Initially, rats had free access to standard pellets (10 g of standard food per 100 g body weight) and water. After one week of adaptable feeding, we added 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar to standard pellets to induce the NAFLD model in the inducible-NAFLD group. The experiments went on for ten weeks, and blood samples were taken from the heart after the rats were sacrificed by inhaling CO₂. To perform the biochemical analysis, the serum was isolated from blood samples and immediately stored at -80°C. Moreover, tissue samples were isolated and immediately stored at -80°C for H&E staining. Besides, the body weight of each rat was recorded weekly.

|

Table 1. Percentage of nutrient ingredients of standard pellets

.PNG) |

To determine the serum level of triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TCH), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), albumin, and fasting blood glucose (FBS), we used an enzymatic assay through biochemical kits (Mindray BS 480, China) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Also, IL-6 serum level was determined by the chemiluminescence assay method (IMMULITE 2000 Xpi, USA).

Histopathological test

In our study, we employed Hematoxylin and Eosin (H and E) staining to assess the pathology of rat liver. The liver tissues were initially fixed in 10% formalin for 1 hour and subsequently dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Thin sections, measuring 8-10 µm, were obtained from the paraffin-embedded tissues using cryosection techniques (17,18). Following the removal of paraffin, the liver sections were subjected to H&E staining (18) to enable examination under a light microscope for pathological analysis (19). In detail, we performed H and E staining on 5 sections per rat and then randomly selected 10 microscopic fields to investigate the morphological changes in liver tissues. This approach allowed us to precisely assess the pathological characteristics. Additionally, to evaluate the presence of lipid droplets, we utilized Oil Red O (ORO) staining (18). To identify lipid droplets in liver tissue, frozen sections were stained with Oil Red O solution for 15 minutes, then washed with 60% isopropanol and counterstained with hematoxylin. Under the microscope, lipids were observed in red and nuclei in blue. This method can only be applied to frozen tissues because the paraffin deparaffinization process causes lipids to dissolve. Under light microscope assessment, lipid droplets appeared red, while the nuclei were stained blue (19). We determined macrovesicular steatosis grades in the NAFLD-induced group using the following scales: Grade zero, absence of steatosis; grade one, up to 30% of hepatocytes affected; grade two, 30 - 70% of hepatocytes affected; grade three, more than 70% of hepatocytes affected (20).

In this study, solid vegetable oil (Hydrogenated) of palm origin with a purity of 99.8% was used, which was obtained from the local market in Iran. This oil was without any antioxidant or preservative additives. The solid sugar used was prepared from sucrose varieties with a purity of 99.9% (Produced from sugar beet), which was obtained from the same source. The purity of the materials was determined using the manufacturer's certificate of analysis and in accordance with the National Standards of Iran (ISIRI) for vegetable oil (ISI 4094) and sugar (ISIRI 2685). Control group rats were fed a standard basal diet (Commercial pellet containing approximately 3.6% fat, 22% protein, and 50% carbohydrate) for 10 weeks. NAFLD model rats received a combination supplement containing 30% hydrogenated solid vegetable oil (Palm origin) and 10% solid sugar (Sucrose) in addition to the basal diet (21). In this study, histopathological evaluations were performed in a blinded manner by pathologists who were unaware of the animal grouping.

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine the normality of the data. The Levene test was used to determine the homogeneity of the data. Comparisons were made using the independent Student's t-test for two groups (SPSS V.22, New York, USA). Values were determined as Mean ± SEM and were used for analysis throughout the experiment. The significance level was set at P-Value<0.05.

Results

Weight/Time progress and abdominal circumference

To determine the effect of consumption of 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar on weight gain, we evaluated the weight/time progress in the NAFLD-induced group compared to the control group (Figure 1A). The obtained results revealed a significantly increased weight/time progress in the treatment group (0.679 g ± 0.02, P-Value < 0.001) compared to the control group (0.559 g ± 0.03). Based on these results, the weight/time progress of NAFLD-induced rats was higher than that of the control group, indicating that the high-fat/high-sugar diet caused an increase in fat mass in the NAFLD-induced rats.

Additionally, we measured the abdominal circumference at the beginning of the experiment and after ten weeks in both experimental (NAFLD-induced) and control rats. The results illustrated a significant difference in abdominal size between the experimental rats (17.93 cm ± 1.18) and controls (14.82 cm ± 14.82). Furthermore, we calculated the abdominal-to-chest size ratio in both groups. The results showed a significant difference between the NAFLD-induced group (1.17 ± 0.05) and controls (1.07 ± 0.05; Figure 1B). Therefore, these results indicate that the high-fat/high-sugar diet induced abdominal fat accumulation in the experimental group compared to controls.

Effect of high fat/high sugar on glucose serum level

The effect of consuming 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar for ten weeks suggested that glucose intolerance may occur and indirectly increase the incidence of insulin resistance. Fasting blood glucose (FBS (mg/dL)) was significantly increased in NAFLD rats (129.6 ± 32.26, P-Value = 0.001) compared with the control group (67.6 ± 37.91; Figure 2). In conclusion, these data suggest that consuming a high-fat/high-sugar diet could lead to insulin resistance and impaired fasting glucose.

Effect of high fat/high sugar on lipid profile parameters for dyslipidemia

The consumption of a high-fat/high-sugar diet significantly increased TG and CH serum levels in NAFLD-induced rats compared with control rats after ten weeks: 65.400 ± 17.12, P-Value = 0.005; 190.500 ± 29.23, P-Value = 0.001, respectively, compared with the control group: 42.400 ± 14.77 and 138.200 ± 23.74 (Figures 3A and 3B). As expected, these data support the lipid accumulation hypothesis in NAFLD-induced rat livers.

Serum levels of HDL, c-LDL, and v-LDL were also significantly altered in NAFLD-induced rats compared with healthy rats after ten weeks: 48.600 ± 30.86, P-Value = 0.014; 137.400 ± 70.83, P-Value = 0.008; and 13.08 ± 3.42, P-Value = 0.005, respectively, compared with the control group: 96.200 ± 38.45, 63.300 ± 34.99, and 8.48 ± 2.95 (Figures 4A, 4B, and 4C). Our results suggest that increasing 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar in the standard pellet diet is reflected in an elevation in serum lipid profile parameters.

Moreover, the atherogenic index and risk factor were assessed by formula. The results showed a significant increase in NAFLD-induced rats compared to healthy rats. The values of the atherogenic index (c-LDL/HDL) were 4.18 ± 4.00, P-Value = 0.03, and the risk factor (CH/HDL) was 5.74 ± 3.93, P-Value = 0.006 (Figures 5A and 5B). Briefly, the 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar diet could increase coronary atherosclerosis and heart attack risk in NAFLD-induced rats compared to controls.

Furthermore, our findings indicated that the TG/HDL-C ratio and TG serum levels - known markers of insulin resistance - were significantly increased in the NAFLD-induced rats compared to controls. The TG/HDL-C ratio of NAFLD-induced rats was 1.84 ± 1.12 g, whereas in controls it was 0.62 ± 0.55 g, with P-Value = 0.006 considered significant (Figure 5C).

Effect of High fat/high sugar on hepatic enzymes and albumin serum levels

We found that the ALT and AST serum levels of the treatment group were influenced by the 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar regimen. After ten weeks of treatment in the NAFLD-induced group, the serum levels of ALT and AST (IU/L) were significantly increased (349.44 ± 45.3, P-Value = 0.001; and 109.84 ± 24.61, P-Value = 0.001, respectively) compared to healthy Wistar rats (221.95 ± 65.63; and 73.12 ± 17.33, respectively; Figures 6A and 6B). The increases in ALT and AST serum levels indicated hepatic steatosis in NAFLD model rats (Figure 6C). As well, the serum level of ALT was higher than the AST level. Additionally, the obtained results illustrated that the serum level of albumin (g/dl) was decreased in NAFLD-induced rats (3.00 ± 0.65, P-Value = 0.004) compared to controls (3.88 ± 0.50; Figure 7A).

.PNG) Figure 1. (A) weight/time (g/day) progress with confidence interval (CI), and (B) abdominal circumference CI (cm) and mean values illustrated between NAFLD-induced and healthy rats; P-Value < 0.05 and a CI equal to 95% were considered significant. |

.PNG) Figure 2. Fasting blood sugar (FBS, mg/dL) serum levels shown in NAFLD-induced compared to healthy rats; P-Value < 0.05 and a CI equal to 95% were considered significant. |

According to the role of interleukin-6 (IL-6) in the progression of NAFLD, we assessed the IL-6 serum level in both groups. In this regard, the serum level of IL-6 was determined by sandwich ELISA. The obtained results revealed that IL-6 levels were significantly increased in NAFLD-induced rats (1.95 ± 0.43 pg/mL, P-Value = 0.004) compared to controls (1.38 ± 0.32 pg/mL; Figure 7B). This was associated with NAFLD induction in NAFLD-induced rats. This result indicates that IL-6 may be a biomarker to describe the risk of NAFLD. The cause of this finding may be that fatty liver itself induces a local subacute inflammatory state characterized by the production of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α or IL-6. These mediators directly contribute to hepatic and systemic insulin resistance (22).

Histopathological results confirmed grade two of hepatic steatosis in high fat/high sugar rats

Examination of sections obtained from livers of the healthy group showed normal histological structure. Predominantly, NAFLD is characterized by macrovesicular steatosis that is usually present in grade two. NASH is described by the presence of hepatocellular ballooning, inflammation, and finally fibrosis in the context of a steatotic liver. After ten weeks on the diet, the results obtained from H and E (Figure 8A) and Oil Red O (Figure 8B) staining illustrated that the Wistar rats developed grade two hepatic steatosis with hepatocyte ballooning compared to the control group with grade zero and no lobular inflammation or hepatocyte ballooning (Table 2). These data revealed that treatment with a high fat/high sugar diet could induce NAFLD in Wistar rats compared to controls.

Figure 3. (A) triglyceride (TG) and (B) cholesterol (CH) serum levels demonstrated in NAFLD-induced compared to healthy rats; P-Value < 0.05 and a CI equal to 95% were considered significant.  Figure 4. (A) High-density lipoprotein (HDL, mg/dL), (B) low-density lipoprotein (LDL, mg/dL), and (C) very low-density lipoprotein (v-LDL, mg/dL) serum levels illustrated in NAFLD-induced compared to healthy rats; P-Value < 0.05 and a CI equal to 95% were considered significant.  Figure 5. (A) atherogenic factor (LDL/HDL ratio), (B) cardiovascular health and the risk of heart disease (TG/HDL ratio), and (C) risk factor (CH/HDL ratio) demonstrated; atherogenic factors and risk factors associated with cardiovascular diseases were analyzed (P-Value < 0.05 and a CI equal to 95% were considered significant). |

Figure 6. (A) ALT, (B) AST, and (C) comparison of ALT and AST serum levels between groups demonstrated in NAFLD-induced compared to healthy rats; P-Value < 0.05 and a CI equal to 95% were considered significant.  Figure 7. (A) albumin (g/dL) serum levels indicated in NAFLD-induced compared to healthy rats (P < 0.05 and a CI equal to 95% were considered significant); and (B) IL-6 (pg/mL) serum levels illustrated in NAFLD-induced compared to healthy rats (P-Value < 0.05 and a CI equal to 95% were considered significant).  Figure 8. Representative photomicrographs of liver sections from control and NAFLD-induced Wistar rats: (A) control liver shows normal hepatic architecture with intact hepatocyte cords, clear sinusoids, and absence of fat vacuoles; (B) NAFLD liver displays macrovesicular and microvesicular steatosis (Black arrows), ballooning of hepatocytes, and mild inflammatory infiltration. Oil Red O staining demonstrates numerous red-stained lipid droplets within hepatocytes of NAFLD rats, while control liver shows no lipid deposition (Scale bar = 50 μm, magnification: ×40). |

|

Table 2. Comparison of steatosis, lobular inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning measurements between control and NAFLD-induced Wistar rat groups

|

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to investigate the effect of a diet containing 30% vegetable oil combined with 10% solid sugar on NAFLD induction in Wistar rats. This study showed that a diet high in vegetable oil and solid sugar, similar to the current human dietary pattern, was able to induce obesity-related NAFLD in Wistar rats, characterized histologically by hepatic steatosis and ballooning of cells. Hepatic changes were clinically characterized by increased TC, and weight/time and metabolic progression were demonstrated by hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, decreased serum albumin, increased IL-6, and elevated serum levels of liver enzymes.

The present findings of steatosis, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and elevated inflammatory markers align with the established pathophysiology through which high-fat/high-sucrose diets promote NAFLD. The combination of saturated fat (From solid vegetable oil) and sucrose acts synergistically via several mechanisms to drive hepatic lipid accumulation and hepatocyte stress. Firstly, high sucrose intake (Hydrolyzed to glucose and fructose) significantly upregulates hepatic de novo lipogenesis (DNL) by activating key transcriptional factors such as ChREBP (23,24). Fructose, in particular, bypasses the tight metabolic regulation of glucose and is rapidly metabolized in the liver, providing ample substrates for DNL (25). Secondly, dietary saturated fat not only provides a direct source of fatty acids for hepatic storage but also promotes peripheral insulin resistance (e.g., in adipose tissue and muscle). This leads to an increased influx of non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) into the liver, providing further substrate for triglyceride synthesis and steatosis (22). Thirdly, this metabolic milieu (Insulin resistance and enhanced DNL) induces oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, as indicated by the elevated liver enzymes (ALT and AST) in our model. This stress activates pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, which we found significantly elevated, creating a vicious cycle that perpetuates both systemic inflammation and hepatic insulin resistance (26).

Thus, our model, by mimicking a relevant human dietary pattern, simultaneously targets key drivers of NAFLD pathogenesis-increased hepatic lipid load, impaired insulin signaling, and inflammatory stress-making it a translationally relevant model for studying this complex disease. Despite the value of existing models, many fail to recapitulate this multifaceted pathophysiology (27).

As well, fewer studies have induced NAFLD in rodents by the simultaneous use of solid sugar and vegetable oil, but in this study, we induced NAFLD through a diet containing 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar for ten weeks in Wistar rats. Other animal studies have described the rapid induction of obesity due to the administration of a high-calorie, high-fructose, and/or high-fat diet, either as a liquid in a food dish or via a nasogastric tube. In contrast, we produced a diet balanced in protein, lipid, carbohydrate, vitamin, and mineral content, which was highly palatable and high in fiber. Practically, we fed animals with a diet very similar to a normal diet both in content and form of administration. In our study, free access to a diet containing 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar was available for NAFLD-induced rats (28,29).

The hyperinsulinemia caused hepatocytes to produce more fatty acids, and triglyceride accumulation in hepatocytes subsequently led to steatosis. It is important to note that a diet with high carbohydrate content aggravates de novo hepatic lipogenesis and plays a critical role in glucose homeostasis, accelerating the development of hypertriglyceridemia and hyperinsulinemia (23,24). Specifically, when the amount of carbohydrates consumed exceeds the total caloric requirement, the rate of de novo hepatic lipogenesis increases more than 10-fold (25). Likewise, it increases 27-fold by consuming a high-carbohydrate diet compared to low-carbohydrate diets and/or fasting (25).

Also, our results have shown that the high-fat/high-sugar diet could increase cardiovascular diseases and was associated with augmentation of atherogenic factors in NAFLD model rats (30). In addition, due to the pro-atherogenic lipid profile, this disease is associated with increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, which we also found in our study (31).

Since we illustrated decreased serum levels of albumin in NAFLD model rats compared to controls, however, it was not significant. The serum level of albumin was associated with NAFLD induction and impaired glucose tolerance. There is a positive correlation between serum albumin level and metabolic syndrome or metabolic risk factors such as lipid profile and BMI. This finding suggests that serum albumin level is associated with insulin resistance (31-33). Aligning with our study, several studies have shown a protective effect of albumin on cardiovascular health, as low levels of serum albumin were associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease, cardiovascular mortality, and carotid atherosclerosis (32,34). One possible explanation for this association is the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of serum albumin. Chronic inflammation plays an essential role in causing insulin resistance and the occurrence of NAFLD (32,34). The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory characteristics of serum albumin in the atherogenic process are suggested as possible mechanisms for this association. As well, chronic inflammation plays essential roles in the generation of both insulin resistance and NAFLD (35-38).

Furthermore, our results illustrated that the serum levels of AST and ALT increased in rats that received the NAFLD-induced diet, indicating successful establishment of the NAFLD model. Previous studies have shown that mild to moderate serum AST and ALT levels increase in patients with NAFLD (39). Several studies demonstrated that the biochemical pattern in hepatic steatosis due to NAFLD is characterized by increased levels of transaminases, with ALT levels exceeding those of AST. Consequently, our results revealed that the serum level of ALT was higher than AST in NAFLD model rats, confirming the formation of steatosis in NAFLD model hepatic tissue (40,41).

Hepatic steatosis and hepatocellular ballooning-early stages of NAFLD-were present in all liver samples of the rats from week 10. At the final stage of the investigation, grade 2 steatosis was observed at week 10. Moreover, fatty droplet formation, confirmed by Oil Red O staining, indicated hepatic injury and lipid accumulation in NAFLD model rats. However, the study duration may not have been long enough to allow for more severe steatosis and histological changes to characterize NASH. Since the liver lesions that occur in NAFLD are associated with the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the liver such as IL-6, our results illustrated that the serum levels of IL-6 increased in NAFLD rats compared to controls.

Furthermore, histopathological examination provided detailed visualization of liver architecture in both groups. The control group exhibited normal lobular organization, with intact hepatocyte cords, distinct sinusoids, and no evidence of lipid accumulation or ballooning degeneration. In contrast, liver sections from NAFLD-induced rats showed marked macrovesicular and microvesicular steatosis, characterized by large cytoplasmic fat vacuoles displacing the nuclei to the cell periphery. Ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes and mild inflammatory cell infiltration were also observed. Oil Red O staining confirmed the presence of abundant red-stained lipid droplets within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes, consistent with fat accumulation and hepatic injury. These observations confirmed the successful induction of grade II hepatic steatosis. Scale bars represent 50 μm in all histological images.

Furthermore, we observed steatosis and hepatocellular ballooning denoting cell injury, revealing NASH histologically. Subsequently, the model presented in this study illustrated that a diet containing 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar induces NAFLD, which is associated with elevated serum levels of FBS, lipid profile, ALT, AST, IL-6, and weight/time progress. Moreover, the incidence of NAFLD in treated rats compared to the control group was confirmed by H&E and Oil Red O staining. The 10-week duration of this study may not fully replicate advanced human NASH with fibrosis, and the exclusive use of male rats limits understanding of gender differences.

Conclusion

In this study, we developed the NAFLD model in rats through the administration of standard pellets supplemented with 30% vegetable oil and 10% solid sugar and obtained biochemical and histological results that confirmed the formation of grade 2 steatosis in NAFLD model rats.

Future directions

Future research should include longer studies to observe fibrosis progression, include female subjects to examine gender disparities, and perform molecular analyses to elucidate underlying pathways.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Golestan, Iran, for providing the facility for performing the animal experiments.

Funding sources

This study was supported by Golestan University of Medical Sciences under grant number [Ethic code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1402.063], which had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Ethical statement

All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (IR.GOUMS.REC.1402.063). The study was conducted in full compliance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

J.A. and A.A. Designed and implemented the study. A.A, and B.A. Performed the experiments and collected the data. A.A. and Z.M. Performed the analysis and interpretation of the data. Z.M. Drafted the manuscript. A.A., Z.M., and B.A. Critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Editorial: Original article |

Subject:

Health

Received: 2025/04/5 | Accepted: 2025/06/8 | Published: 2025/06/21

Received: 2025/04/5 | Accepted: 2025/06/8 | Published: 2025/06/21

References

1. Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, Underwood FE, King JA, Afshar EE, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(9):851-61. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

2. Karjoo S, Auriemma A, Fraker T, Bays HE. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and obesity: An Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) Clinical Practice Statement (CPS) 2022. Obes Pillars. 2022;3:100027. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

3. Huh Y, Cho YJ, Nam GE. Recent epidemiology and risk factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2022;31(1):17-27. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Motamed N, Khoonsari M, Panahi M, Rezaie N, Maadi M, Safarnezhad Tameshkel F, et al. The incidence and risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a cohort study from Iran. Hepat Mon. 2020;20(2):e98531. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

5. Berná G, Rodríguez-García M. The role of nutrition in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: pathophysiology and management. Liver Int. 2020;40 Suppl 1:102-8. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

6. Gaggini M, Morelli M, Buzzigoli E, et al. NAFLD as a continuum: from obesity to metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020;12:60. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Scapaticci S, D'Adamo E, Mohn A, Chiarelli F, Giannini C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese youth with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:639548. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Wentworth BJ, Caldwell SH. Pearls and pitfalls in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: tricky results are common. Metab Target Organ Damage. 2021;1(1):2. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

9. Zhong F, Zhou X, Xu J, Gao L. Rodent models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Digestion. 2020;101(5):522-35. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

10. Vvedenskaya O, Rose TD, Knittelfelder O, Palladini A, Wodke JAH, Schuhmann K, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease stratification by liver lipidomics. J Lipid Res. 2021;62:100104. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. Radhakrishnan S, Ke J-Y, Pellizzon MA. Targeted nutrient modifications in purified diets differentially affect nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic disease development in rodent models. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020;4(6):nzaa078. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

12. Zhang H, Léveillé M, Courty E, Gunes A, Nguyen BN, Estall JL, et al. Differences in metabolic and liver pathobiology induced by two dietary rat models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;319(5):E863-E8. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

13. Chyau C-C, Wang H-F, Zhang W-J, Chen C-C, Huang S-H, Chang C-C, et al. Antrodan alleviates high-fat and high-fructose diet-induced fatty liver disease in C57BL/6 rats via AMPK/Sirt1/SREBP-1c/PPARγ pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(1):360. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

14. Ragab SM, Abd Elghaffar SK, El-Metwally TH, Badr G, Mahmoud MH, Omar HM. Effect of a high fat, high sucrose diet on the promotion of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in male rats: the ameliorative role of three natural compounds. Lipids Health Dis. 2015;14:83. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

15. Ishimoto T, Lanaspa MA, Rivard CJ, Roncal-Jimenez CA, Orlicky DJ, Cicerchi C, et al. High-fat and high-sucrose (western) diet induces steatohepatitis that is dependent on fructokinase. Hepatology. 2013;58(5):1632-1643. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

16. Torres-Villalobos G, Hamdan-Pérez N, Tovar AR, Ordaz-Nava G, Martínez-Benítez B, Torre-Villalvazo I, et al. Combined high-fat diet and sustained high sucrose consumption promotes NAFLD in a murine model. Ann Hepatol. 2015;14(4):540-6. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

17. Farokhcheh M, Hejazian L, Akbarnejad Z, Pourabdolhossein F, Hosseini SM, Mehraei TM, et al. Geraniol improved memory impairment and neurotoxicity induced by zinc oxide nanoparticles in male Wistar rats through its antioxidant effect. Life Sci. 2021;282:119824. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

18. Bancroft JD, Gamble M. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 5th ed. London: Elsevier; 2002. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

19. Wong SK, Chin K-Y, Ahmad F, Ima-Nirwana S. Biochemical and histopathological assessment of liver in a rat model of metabolic syndrome induced by high-carbohydrate high-fat diet. J Food Biochem. 2020;44(10):e13367. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

20. Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41(6):1313-21. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

21. Ngala RA, Ampong I, Saky SA, Anto EO. Effect of dietary vegetable oil consumption on blood glucose levels, lipid profile and weight in diabetic rat: an experimental case-control study. BMC Nutr. 2016;2:28. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

22. Parekh S, Anania FA. Abnormal lipid and glucose metabolism in obesity: implications for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2191-207. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

23. Sparks JD, Sparks CE, Adeli K. Selective hepatic insulin resistance, VLDL overproduction, and hypertriglyceridemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(9):2104-12. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

24. Schwarz J-M, Linfoot P, Dare D, Aghajanian K. Hepatic de novo lipogenesis in normoinsulinemic and hyperinsulinemic subjects consuming high-fat, low-carbohydrate and low-fat, high-carbohydrate isoenergetic diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(1):43-50. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

25. Hudgins LC, Hellerstein MK, Seidman CE, Neese RA, Tremaroli JD, Hirsch J. Relationship between carbohydrate-induced hypertriglyceridemia and fatty acid synthesis in lean and obese subjects. J Lipid Res. 2000;41(4):595-604. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

26. Wieckowska A, Papouchado BG, Li Z, Lopez R, Zein NN, Feldstein AE. Increased hepatic and circulating interleukin-6 levels in human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(6):1372-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

27. Li Y, Tran VH, Kota BP, Nammi S, Duke CC, Roufogalis BD. Preventative effect of Zingiber officinale on insulin resistance in a high-fat high-carbohydrate diet-fed rat model. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;115(2):209-15. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

28. Marchesini G, Brizi M, Morselli-Labate AM, Bianchi G, Bugianesi E, McCullough AJ, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance. Am J Med. 1999;107(5):450-5. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

29. Paschos P, Paletas K. Non alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome. Hippokratia. 2009;13(1):9-19. [View at Publisher] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

30. Villanova N, Moscatiello S, Ramilli S, Bugianesi E, Magalotti D, Vanni E, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular risk profile in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42(2):473-80. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

31. Ishizaka N, Ishizaka Y, Nagai R, Toda E-l, Hashimoto H, Yamakado M. Association between serum albumin, carotid atherosclerosis, and metabolic syndrome in Japanese individuals. 2007;193(2):373-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

32. Danesh J, MuirJ, Wong YK, Ward M, Gallimore JR, Pepys MB. Risk factors for coronary heart disease and acute-phase proteins. A population-based study. Eur Heart J. 1999;20(13):954-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

33. Saito I, Yonemasu K, Inami F. Association of body mass index, body fat, and weight gain with inflammation markers among rural residents in Japan. Circ J. 2003;67(4):323-9 [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

34. Danesh J, Collins R, Appleby P, Peto R. Association of fibrinogen and C-reactive protein with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1998;279(18):1477-82. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

35. Ceriello A, Motz E. Is oxidative stress the pathogenic mechanism underlying insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease? The common soil hypothesis revisited. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(5):816-23. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

36. Tarantino G, Caputi A. JNKs, insulin resistance and inflammation: A possible link between NAFLD and coronary artery disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(33):3785-94. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

37. Zhao D, Cui H, Shao Z, Cao L. Abdominal obesity, chronic inflammation and the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2023;28(4):100726. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

38. Asrih M, Jornayvaz FR. Inflammation as a potential link between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance. J Endocrinol. 2013;218(3):R25-R36. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

39. Angulo P, Keach JC, Batts KP, Lindor KD. Independent predictors of liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 1999;30(6):1356-62. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

40. Marchesini G, Moscatiello S, Di Domizio S, Forlani G. Obesity-associated liver disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11 Suppl 1):S74-S80. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

41. Sorbi D, Boynton J, Lindor KD. The ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase: potential value in differentiating nonalcoholic steatohepatitis from alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(4):1018-22. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |